Geometry of interaction

(Execution formula : false assertion corrected) |

(corrections, precisions) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

== Preliminaries == |

== Preliminaries == |

||

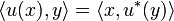

| − | We begin by a brief tour of the operations in Hilbert spaces that we use. In this article <math>H</math> will stand for the Hilbert space <math>\ell^2(\mathbb{N})</math> of sequences <math>(x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> of complex numbers such that the series <math>\sum_{n\in\mathbb{N}}|x_n|^2</math> converges. If <math>x = (x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> and <math>y = (y_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> are two vectors of <math>H</math> we denote by <math>\langle x,y\rangle</math> their scalar product: |

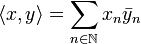

+ | We will denote by <math>H</math> the Hilbert space <math>\ell^2(\mathbb{N})</math> of sequences <math>(x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> of complex numbers such that the series <math>\sum_{n\in\mathbb{N}}|x_n|^2</math> converges. If <math>x = (x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> and <math>y = (y_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> are two vectors of <math>H</math> their ''scalar product'' is: |

: <math>\langle x, y\rangle = \sum_{n\in\mathbb{N}} x_n\bar y_n</math>. |

: <math>\langle x, y\rangle = \sum_{n\in\mathbb{N}} x_n\bar y_n</math>. |

||

| − | Two vectors of <math>H</math> are ''othogonal'' if their scalar product is nul. We will say that two subspaces are ''disjoint'' when their vectors are pairwise orthogonal; this terminology is slightly misleading as disjoint subspaces always have <math>0</math> in common. |

+ | Two vectors of <math>H</math> are ''othogonal'' if their scalar product is nul. We will say that two subspaces are ''disjoint'' when any two vectors taken in each subspace are orthorgonal. Note that this notion is different from the set theoretic one, in particular two disjoint subspaces always have exactly one vector in common: <math>0</math>. |

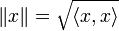

The ''norm'' of a vector is the square root of the scalar product with itself: |

The ''norm'' of a vector is the square root of the scalar product with itself: |

||

: <math>\|x\| = \sqrt{\langle x, x\rangle}</math>. |

: <math>\|x\| = \sqrt{\langle x, x\rangle}</math>. |

||

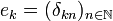

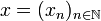

| − | Let us denote by <math>(e_k)_{k\in\mathbb{N}}</math> the canonical hilbertian basis of <math>H</math>: <math>e_k = (\delta_{kn})_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> where <math>\delta_{kn}</math> is the Kroenecker symbol: <math>\delta_{kn}=1</math> if <math>k=n</math>, <math>0</math> otherwise. Thus if <math>x=(x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> is a sequence in <math>H</math> we have: |

+ | Let us denote by <math>(e_k)_{k\in\mathbb{N}}</math> the canonical ''hilbertian basis'' of <math>H</math>: <math>e_k = (\delta_{kn})_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> where <math>\delta_{kn}</math> is the Kroenecker symbol: <math>\delta_{kn}=1</math> if <math>k=n</math>, <math>0</math> otherwise. Thus if <math>x=(x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> is a sequence in <math>H</math> we have: |

: <math> x = \sum_{n\in\mathbb{N}} x_ne_n</math>. |

: <math> x = \sum_{n\in\mathbb{N}} x_ne_n</math>. |

||

| − | An ''operator'' on <math>H</math> is a ''continuous'' linear map from <math>H</math> to <math>H</math>. Continuity is equivalent to the fact that operators are ''bounded'', which means that one may define the ''norm'' of an operator <math>u</math> as the sup on the unit ball of the norms of its values: |

+ | An ''operator'' on <math>H</math> is a ''continuous'' linear map from <math>H</math> to <math>H</math><ref>Continuity is equivalent to the fact that operators are ''bounded'', which means that one may define the ''norm'' of an operator <math>u</math> as the sup on the unit ball of the norms of its values: |

| − | : <math>\|u\| = \sup_{\{x\in H,\, \|x\| = 1\}}\|u(x)\|</math>. |

+ | : <math>\|u\| = \sup_{\{x\in H,\, \|x\| = 1\}}\|u(x)\|</math>.</ref>. The set of (bounded) operators is denoted by <math>\mathcal{B}(H)</math>. |

| − | |||

| − | The set of (bounded) operators is denoted by <math>\mathcal{B}(H)</math>. |

||

The ''range'' or ''codomain'' of the operator <math>u</math> is the set of images of vectors; the ''kernel'' of <math>u</math> is the set of vectors that are anihilated by <math>u</math>; the ''domain'' of <math>u</math> is the set of vectors orthogonal to the kernel, ''ie'', the maximal subspace disjoint with the kernel: |

The ''range'' or ''codomain'' of the operator <math>u</math> is the set of images of vectors; the ''kernel'' of <math>u</math> is the set of vectors that are anihilated by <math>u</math>; the ''domain'' of <math>u</math> is the set of vectors orthogonal to the kernel, ''ie'', the maximal subspace disjoint with the kernel: |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

These three sets are closed subspaces of <math>H</math>. |

These three sets are closed subspaces of <math>H</math>. |

||

| − | The ''adjoint'' of an operator <math>u</math> is the operator <math>u^*</math> defined by <math>\langle u(x), y\rangle = \langle x, u^*(y)\rangle</math> for any <math>x,y\in H</math>. Adjointness if well behaved w.r.t. composition of operators: |

+ | The ''adjoint'' of an operator <math>u</math> is the operator <math>u^*</math> defined by <math>\langle u(x), y\rangle = \langle x, u^*(y)\rangle</math> for any <math>x,y\in H</math>. Adjointness is well behaved w.r.t. composition of operators: |

: <math>(uv)^* = v^*u^*</math>. |

: <math>(uv)^* = v^*u^*</math>. |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

A ''partial isometry'' is an operator <math>u</math> satisfying <math>uu^* u = |

A ''partial isometry'' is an operator <math>u</math> satisfying <math>uu^* u = |

||

u</math>; this condition entails that we also have <math>u^*uu^* = |

u</math>; this condition entails that we also have <math>u^*uu^* = |

||

| − | u^*</math>. As a consequence <math>uu^*</math> and <math>uu^*</math> are both projectors, called respectively the ''initial'' and the ''final'' projector of <math>u</math> because their codomain are respectively the domain and the codomain of <math>u</math>. The restriction of <math>u</math> to its domain is an isometry. Projectors are particular examples of partial isometries. |

+ | u^*</math>. As a consequence <math>uu^*</math> and <math>uu^*</math> are both projectors, called respectively the ''initial'' and the ''final'' projector of <math>u</math> because their (co)domains are respectively the domain and the codomain of <math>u</math>: |

| + | * <math>\mathrm{Dom}(u^*u) = \mathrm{Codom}(u^*u) = \mathrm{Dom}(u)</math>; |

||

| + | * <math>\mathrm{Dom}(uu^*) = \mathrm{Codom}(uu^*) = \mathrm{Codom}(u)</math>. |

||

| + | |||

| + | The restriction of <math>u</math> to its domain is an isometry. Projectors are particular examples of partial isometries. |

||

If <math>u</math> is a partial isometry then <math>u^*</math> is also a partial isometry the domain of which is the codomain of <math>u</math> and the codomain of which is the domain of <math>u</math>. |

If <math>u</math> is a partial isometry then <math>u^*</math> is also a partial isometry the domain of which is the codomain of <math>u</math> and the codomain of which is the domain of <math>u</math>. |

||

| − | If the domain of <math>u</math> is <math>H</math> that is if <math>u^* u = 1</math> we say that <math>u</math> has ''full domain'', and similarly for codomain. If <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are two partial isometries, the equation <math>uu^* + vv^* = 1</math> means that the codomains of <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are disjoint and that their direct sum is <math>H</math>. |

+ | If the domain of <math>u</math> is <math>H</math> that is if <math>u^* u = 1</math> we say that <math>u</math> has ''full domain'', and similarly for codomain. If <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are two partial isometries, the equation <math>uu^* + vv^* = 1</math> means that the codomains of <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are disjoint but their direct sum is <math>H</math>. |

=== Partial permutations and partial isometries === |

=== Partial permutations and partial isometries === |

||

| − | We will now define our proof space which turns out to be the set of partial isometries acting as permutations on a fixed basis of <math>H</math>. |

+ | We will now define our proof space which turns out to be the set of partial isometries acting as permutations on the canonical basis <math>(e_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math>. |

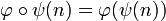

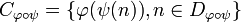

| − | More precisely a ''partial permutation'' <math>\varphi</math> on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> is a function defined on a subset <math>D_\varphi</math> of <math>\mathbb{N}</math> which is one-to-one onto a subset <math>C_\varphi</math> of <math>\mathbb{N}</math>. <math>D_\varphi</math> is called the ''domain'' of <math>\varphi</math> and <math>C_\varphi</math> its ''codomain''. Partial permutations may be composed: if <math>\psi</math> is another partial permutation on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> then <math>\varphi\circ\psi</math> is defined by: |

+ | More precisely a ''partial permutation'' <math>\varphi</math> on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> is a one-to-one map defined on a subset <math>D_\varphi</math> of <math>\mathbb{N}</math> onto a subset <math>C_\varphi</math> of <math>\mathbb{N}</math>. <math>D_\varphi</math> is called the ''domain'' of <math>\varphi</math> and <math>C_\varphi</math> its ''codomain''. Partial permutations may be composed: if <math>\psi</math> is another partial permutation on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> then <math>\varphi\circ\psi</math> is defined by: |

* <math>n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math> iff <math>n\in D_\psi</math> and <math>\psi(n)\in D_\varphi</math>; |

* <math>n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math> iff <math>n\in D_\psi</math> and <math>\psi(n)\in D_\varphi</math>; |

||

* if <math>n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math> then <math>\varphi\circ\psi(n) = \varphi(\psi(n))</math>; |

* if <math>n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math> then <math>\varphi\circ\psi(n) = \varphi(\psi(n))</math>; |

||

| − | * the codomain of <math>\varphi\circ\psi</math> is the image of the domain. |

+ | * the codomain of <math>\varphi\circ\psi</math> is the image of the domain: <math>C_{\varphi\circ\psi} = \{\varphi(\psi(n)), n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}\}</math>. |

Partial permutations are well known to form a structure of ''inverse monoid'' that we detail now. |

Partial permutations are well known to form a structure of ''inverse monoid'' that we detail now. |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

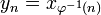

: <math>y_n = x_{\varphi^{-1}(n)}</math> if <math>n\in C_\varphi</math>, <math>0</math> otherwise. |

: <math>y_n = x_{\varphi^{-1}(n)}</math> if <math>n\in C_\varphi</math>, <math>0</math> otherwise. |

||

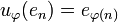

| − | We will (not so abusively) write <math>e_{\varphi(n)} = 0</math> when <math>\varphi(n)</math> is undefined so that may shorten the definition of <math>u_\varphi</math> into: |

+ | We will (not so abusively) write <math>e_{\varphi(n)} = 0</math> when <math>\varphi(n)</math> is undefined so that the definition of <math>u_\varphi</math> reads: |

: <math>u_\varphi(e_n) = e_{\varphi(n)}</math>. |

: <math>u_\varphi(e_n) = e_{\varphi(n)}</math>. |

||

| − | The domain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is the subspace spanned by the family <math>(e_n)_{n\in D_\varphi}</math> and the codomain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is the subspace spanned by <math>(e_n)_{n\in C_\varphi}</math>. As a particular case if <math>\varphi</math> is <math>1_D</math> the partial identity on <math>D</math> then <math>u_\varphi</math> is the projector on the subspace spanned by <math>(e_n)_{n\in D}</math>. |

+ | The domain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is the subspace spanned by the family <math>(e_n)_{n\in D_\varphi}</math> and the codomain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is the subspace spanned by <math>(e_n)_{n\in C_\varphi}</math>. In particular if <math>\varphi</math> is <math>1_D</math> then <math>u_\varphi</math> is the projector on the subspace spanned by <math>(e_n)_{n\in D}</math>. |

{{Proposition| |

{{Proposition| |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

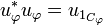

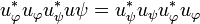

: <math>u^*_\varphi u_\varphi = u_{1_{C_\varphi}}</math>. |

: <math>u^*_\varphi u_\varphi = u_{1_{C_\varphi}}</math>. |

||

| − | Projectors generated by partial identities commute; in particular we have: |

+ | Projectors generated by partial identities commute: |

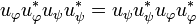

: <math>u_\varphi u_\varphi^*u_\psi u_\psi^* = u_\psi u_\psi^*u_\varphi u_\varphi^*</math>. |

: <math>u_\varphi u_\varphi^*u_\psi u_\psi^* = u_\psi u_\psi^*u_\varphi u_\varphi^*</math>. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| + | Note that this entails all the other commutations of projectors: <math>u^*_\varphi u_\varphi u_\psi u^*\psi = u_\psi u^*_\psi u^*_\varphi u_\varphi</math> and <math>u^*_\varphi u_\varphi u^*_\psi u\psi = u^*_\psi u_\psi u^*_\varphi u_\varphi</math>. |

||

{{Definition| |

{{Definition| |

||

| Line 129: | Line 130: | ||

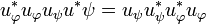

: <math>u+v\in\mathcal{P}</math> iff <math>uu^*vv^* = u^*uv^*v = 0</math>. |

: <math>u+v\in\mathcal{P}</math> iff <math>uu^*vv^* = u^*uv^*v = 0</math>. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| − | Suppose for contradiction that <math>e_n</math> is in the domain of <math>u</math> and in the domain of <math>v</math>. As <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are <math>p</math>-isometries there are integers <math>p</math> and <math>q</math> such that <math>u(e_n) = e_p</math> and <math>v(e_n) = e_q</math> thus <math>(u+v)(e_n) = e_p + e_q</math> which is not a basis vector; therefore <math>u+v</math> is not a <math>p</math>-permutation. |

+ | |

| + | {{Proof| |

||

| + | Suppose for contradiction that <math>e_n</math> is in the domains of <math>u</math> and <math>v</math>. There are integers <math>p</math> and <math>q</math> such that <math>u(e_n) = e_p</math> and <math>v(e_n) = e_q</math> thus <math>(u+v)(e_n) = e_p + e_q</math> which is not a basis vector; therefore <math>u+v</math> is not a <math>p</math>-permutation. |

||

| + | }} |

||

As a corollary note that if <math>u+v=0</math> then <math>u=v=0</math>. |

As a corollary note that if <math>u+v=0</math> then <math>u=v=0</math>. |

||

| Line 158: | Line 159: | ||

: <math>u_{22} = q^*uq</math>. |

: <math>u_{22} = q^*uq</math>. |

||

| − | The <math>u_{ij}</math>'s are called the ''components'' of <math>u</math>. The externalization is functorial in the sense that if <math>v</math> is another operator externalized as: |

+ | The <math>u_{ij}</math>'s are called the ''external components'' of <math>u</math>. The externalization is functorial in the sense that if <math>v</math> is another operator externalized as: |

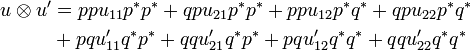

: <math>V = \begin{pmatrix} |

: <math>V = \begin{pmatrix} |

||

v_{11} & v_{12}\\ |

v_{11} & v_{12}\\ |

||

| Line 170: | Line 171: | ||

then the externalization of <math>uv</math> is <math>UV</math>. |

then the externalization of <math>uv</math> is <math>UV</math>. |

||

| − | We also have: |

+ | As <math>pp^* + qq^* = 1</math> we have: |

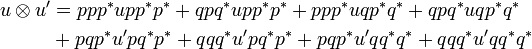

: <math>u = (pp^*+qq^*)u(pp^*+qq^*) = pu_{11}p^* + pu_{12}q^* + qu_{21}p^* + qu_{22}q^*</math> |

: <math>u = (pp^*+qq^*)u(pp^*+qq^*) = pu_{11}p^* + pu_{12}q^* + qu_{21}p^* + qu_{22}q^*</math> |

||

which entails that externalization is reversible, its converse being called ''internalization''. |

which entails that externalization is reversible, its converse being called ''internalization''. |

||

| − | Furthermore if we suppose that <math>u</math> is a <math>p</math>-isometry then so are the components <math>u_{ij}</math>'s. Thus the formula above entails that the four terms of the sum have pairwise disjoint domains and pairwise disjoint codomains. |

+ | If we suppose that <math>u</math> is a <math>p</math>-isometry then so are the components <math>u_{ij}</math>'s. Thus the formula above entails that the four terms of the sum have pairwise disjoint domains and pairwise disjoint codomains from which we deduce: |

| + | |||

{{Proposition| |

{{Proposition| |

||

If <math>u</math> is a <math>p</math>-isometry and <math>u_{ij}</math> are its external components then: |

If <math>u</math> is a <math>p</math>-isometry and <math>u_{ij}</math> are its external components then: |

||

| Line 181: | Line 182: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

| − | As an example of computation in <math>\mathcal{P}</math> let us compute the product of the final projectors of <math>pu_{11}p^*</math> and <math>pu_{12}q^*</math>: |

+ | As an example of computation in <math>\mathcal{P}</math> let us check that the product of the final projectors of <math>pu_{11}p^*</math> and <math>pu_{12}q^*</math> is null: |

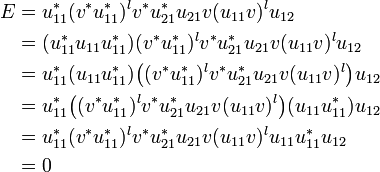

: <math>\begin{align} |

: <math>\begin{align} |

||

(pu_{11}p^*)(pu^*_{11}p^*)(pu_{12}q^*)(qu_{12}^*p^*) |

(pu_{11}p^*)(pu^*_{11}p^*)(pu_{12}q^*)(qu_{12}^*p^*) |

||

| − | &= (pp^*upp^*)(pp^*u^*pp^*)(pp^*uqq^*)(qq^*u^*pp^*)\\ |

+ | &= pu_{11}u_{11}^*u_{12}u_{12}^*p^*\\ |

&= pp^*upp^*u^*pp^*uqq^*u^*pp^*\\ |

&= pp^*upp^*u^*pp^*uqq^*u^*pp^*\\ |

||

&= pp^*u(pp^*)(u^*pp^*u)qq^*u^*pp^*\\ |

&= pp^*u(pp^*)(u^*pp^*u)qq^*u^*pp^*\\ |

||

| Line 195: | Line 196: | ||

== Interpreting the multiplicative connectives == |

== Interpreting the multiplicative connectives == |

||

| − | Recall that when <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are partial isometries in <math>\mathcal{P}</math> we say they are dual when <math>uv</math> is nilpotent, and that <math>\bot</math> denotes the set of nilpotent operators. A ''type'' is a subset of <math>\mathcal{P}</math> that is equal to its bidual. In particular <math>X\orth</math> is a type for any <math>X\subset\mathcal{P}</math>. We say that <math>X</math> ''generates'' the type <math>X\biorth</math>. |

+ | Recall that when <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are <math>p</math>-isometries we say they are dual when <math>uv</math> is nilpotent, and that <math>\bot</math> denotes the set of nilpotent operators. A ''type'' is a subset of <math>\mathcal{P}</math> that is equal to its bidual. In particular <math>X\orth</math> is a type for any <math>X\subset\mathcal{P}</math>. We say that <math>X</math> ''generates'' the type <math>X\biorth</math>. |

=== The tensor and the linear application === |

=== The tensor and the linear application === |

||

| Line 211: | Line 212: | ||

\end{pmatrix}</math> |

\end{pmatrix}</math> |

||

| − | Note that this so-called tensor resembles a sum rather than a product. We will stick to this terminology though because it defines the interpretation of the tensor connective of linear logic. |

+ | {{Remark| |

| + | This so-called tensor resembles a sum rather than a product. We will stick to this terminology though because it defines the interpretation of the tensor connective of linear logic. |

||

| + | }} |

||

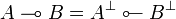

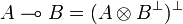

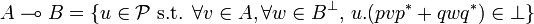

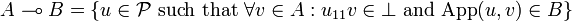

The linear implication is derived from the tensor by duality: given two types <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> the type <math>A\limp B</math> is defined by: |

The linear implication is derived from the tensor by duality: given two types <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> the type <math>A\limp B</math> is defined by: |

||

| Line 221: | Line 222: | ||

=== The identity === |

=== The identity === |

||

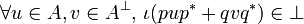

| − | The interpretation of the identity is an example of internalization. Given a type <math>A</math> we are to find an operator <math>\iota</math> in type <math>A\limp A</math>, thus satisfying: |

+ | Given a type <math>A</math> we are to find an operator <math>\iota</math> in type <math>A\limp A</math>, thus satisfying: |

: <math>\forall u\in A, v\in A\orth,\, \iota(pup^* + qvq^*)\in\bot</math>. |

: <math>\forall u\in A, v\in A\orth,\, \iota(pup^* + qvq^*)\in\bot</math>. |

||

| Line 234: | Line 235: | ||

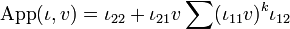

{{Definition| |

{{Definition| |

||

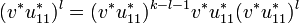

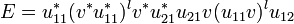

| − | Let <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> be two operators; as above denote by <math>u_{ij}</math> the external components of <math>u</math>. Assume that <math>u_{11}v</math> is nilpotent. We define a new operator <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)</math> by: |

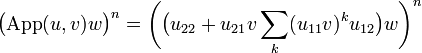

+ | Let <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> be two operators; as above denote by <math>u_{ij}</math> the external components of <math>u</math>. If <math>u_{11}v</math> is nilpotent we define the ''application of <math>u</math> to <math>v</math>'' by: |

| − | : <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v) = u_{22} + u_{21}v\sum_k(u_{11}v)^ku_{11}</math>. |

+ | : <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v) = u_{22} + u_{21}v\sum_k(u_{11}v)^ku_{12}</math>. |

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 281: | Line 282: | ||

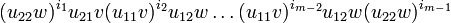

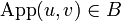

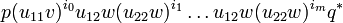

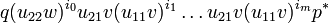

# <math>q(u_{22}w)^{i_0}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_1}\dots u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_m}p^*</math> or |

# <math>q(u_{22}w)^{i_0}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_1}\dots u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_m}p^*</math> or |

||

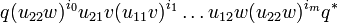

# <math>q(u_{22}w)^{i_0}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_1}\dots u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{i_m}q^*</math>, |

# <math>q(u_{22}w)^{i_0}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_1}\dots u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{i_m}q^*</math>, |

||

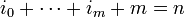

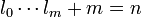

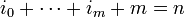

| − | for all tuples of integers <math>(i_1,\dots, i_m)</math> such that <math>i_0+\cdots+i_m+m = n</math>. |

+ | for all tuples of (nonnegative) integers <math>(i_1,\dots, i_m)</math> such that <math>i_0+\cdots+i_m+m = n</math>. |

| − | Each of these monomial is a <math>p</math>-isometry. Furthermore they have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains because their sum is the <math>p</math>-isometry <math>(u.(pvp^* + qwq^*))^n</math>. |

+ | Each of these monomial is a <math>p</math>-isometry. Furthermore they have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains because their sum is the <math>p</math>-isometry <math>(u.(pvp^* + qwq^*))^n</math>. This entails that <math>(u.(pvp^* + qwq^*))^n = 0</math> iff all these monomials are null. |

Suppose <math>u_{11}v</math> is nilpotent and consider: |

Suppose <math>u_{11}v</math> is nilpotent and consider: |

||

: <math>\bigl(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w\bigr)^n = \biggl(\bigl(u_{22} + u_{21}v\sum_k(u_{11}v)^k u_{12}\bigr)w\biggr)^n</math>. |

: <math>\bigl(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w\bigr)^n = \biggl(\bigl(u_{22} + u_{21}v\sum_k(u_{11}v)^k u_{12}\bigr)w\biggr)^n</math>. |

||

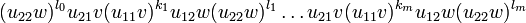

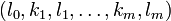

Developping we get a finite sum of monomials of the form: |

Developping we get a finite sum of monomials of the form: |

||

| − | : <math>(u_{22}w)^{l_0}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{k_1}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{l_1}\dots u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{k_m}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{l_m}</math> |

+ | : 5. <math>(u_{22}w)^{l_0}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{k_1}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{l_1}\dots u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{k_m}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{l_m}</math> |

| − | for all tuples <math>(l_0,\dots, l_m)</math> such that <math>l_0\cdots l_m + m = n</math>. |

+ | for all tuples <math>(l_0, k_1, l_1,\dots, k_m, l_m)</math> such that <math>l_0\cdots l_m + m = n</math> and <math>k_i</math> is less than the degree of nilpotency of <math>u_{11}v</math> for all <math>i</math>. |

Again as these monomials are <math>p</math>-isometries and their sum is the <math>p</math>-isometry <math>(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w)^n</math>, they have pairwise disjoint domains and pairwise disjoint codomains. Note that each of these monomial is equal to <math>q^*Mq</math> where <math>M</math> is a monomial of type 4 above. |

Again as these monomials are <math>p</math>-isometries and their sum is the <math>p</math>-isometry <math>(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w)^n</math>, they have pairwise disjoint domains and pairwise disjoint codomains. Note that each of these monomial is equal to <math>q^*Mq</math> where <math>M</math> is a monomial of type 4 above. |

||

| + | |||

| + | As before we thus have that <math>\bigl(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w\bigr)^n = 0</math> iff all monomials of type 5 are null. |

||

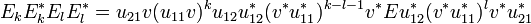

Suppose now that <math>u\in A\limp B</math> and <math>v\in A</math>. Then, since <math>0\in B\orth</math> (<math>0</math> belongs to any type) <math>u.(pvp^*) = pu_{11}vp^*</math> is nilpotent, thus <math>u_{11}v</math> is nilpotent. |

Suppose now that <math>u\in A\limp B</math> and <math>v\in A</math>. Then, since <math>0\in B\orth</math> (<math>0</math> belongs to any type) <math>u.(pvp^*) = pu_{11}vp^*</math> is nilpotent, thus <math>u_{11}v</math> is nilpotent. |

||

| − | Suppose further that <math>w\in B\orth</math>. Then <math>u.(pvp^*+qwq^*)</math> is nilpotent, thus there is a <math>N</math> such that <math>(u.(pvp^* + qwq^*))^n=0</math> for any <math>n\geq N</math>. This entails that all monomials of type 1 to 4 are null because they have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains. Therefore all monomials appearing in the developpment of <math>(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w)^N</math> are null which proves that <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)w</math> is nilpotent. Thus <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)\in B</math>. |

+ | Suppose further that <math>w\in B\orth</math>. Then <math>u.(pvp^*+qwq^*)</math> is nilpotent, thus there is a <math>N</math> such that <math>(u.(pvp^* + qwq^*))^n=0</math> for any <math>n\geq N</math>. This entails that all monomials of type 1 to 4 are null. Therefore all monomials appearing in the developpment of <math>(\mathrm{App}(u,v)w)^N</math> are null which proves that <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)w</math> is nilpotent. Thus <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)\in B</math>. |

| − | Conversely suppose for any <math>v\in A</math> and <math>w\in B\orth</math>, <math>u_{11}v</math> and <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)w</math> are nilpotent. Let <math>P</math> and <math>N</math> be their respective degrees of nilpotency and put <math>n=N(P+1)+N</math>. Then we claim that all monomials appearing in the development of <math>(u.(pvp^*+qwq^*))^n</math> are null. |

+ | Conversely suppose for any <math>v\in A</math> and <math>w\in B\orth</math>, <math>u_{11}v</math> and <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)w</math> are nilpotent. Let <math>P</math> and <math>N</math> be their respective degrees of nilpotency and put <math>n=N(P+1)+N</math>. Then we claim that all monomials of type 1 to 4 appearing in the development of <math>(u.(pvp^*+qwq^*))^n</math> are null. |

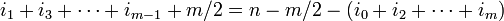

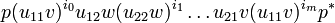

Consider for example a monomial of type 1: |

Consider for example a monomial of type 1: |

||

| − | : <math>p(u_{11}v)^{i_0}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{i_1}\dots u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_m}p^*</math>. |

+ | : <math>p(u_{11}v)^{i_0}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{i_1}\dots u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_m}p^*</math> |

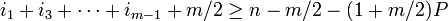

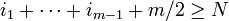

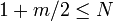

| − | If <math>i_{2k}\geq P</math> for some <math>0\leq k\leq m/2</math> then <math>(u_{11}v)^{i_{2k}}=0</math>. Otherwise if <math>i_{2k}<P</math> for all <math>k</math> then as we have: |

+ | with <math>i_0+\cdots+i_m + m = n</math>. Note that <math>m</math> must be even. |

| − | : <math>i_0+\cdots+i_m + m = n</math> |

+ | |

| − | we deduce: |

+ | If <math>i_{2k}\geq P</math> for some <math>0\leq k\leq m/2</math> then <math>(u_{11}v)^{i_{2k}}=0</math> thus our monomial is null. Otherwise if <math>i_{2k}<P</math> for all <math>k</math> we have: |

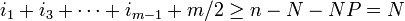

: <math>i_1+i_3+\cdots +i_{m-1} + m/2 = n - m/2 - (i_0+i_2+\cdots +i_m)</math> |

: <math>i_1+i_3+\cdots +i_{m-1} + m/2 = n - m/2 - (i_0+i_2+\cdots +i_m)</math> |

||

thus: |

thus: |

||

| − | : <math>i_1+i_3+\cdots +i_{m-1}\geq n - (m/2)(1+P)</math>. |

+ | : <math>i_1+i_3+\cdots +i_{m-1} + m/2\geq n - m/2 - (1+m/2)P</math>. |

| − | Now if <math>m/2\geq N</math> then <math>i_1+\cdots+i_{m-1}+m/2 \geq N</math>. Otherwise <math>m/2<N</math> and |

+ | Now if <math>m/2\geq N</math> then <math>i_1+\cdots+i_{m-1}+m/2 \geq N</math>. Otherwise <math>1+m/2\leq N</math> thus |

| − | : <math>i_1+i_3+\cdots +i_{m-1}\geq n - N(1+P) = N</math>. |

+ | : <math>i_1+i_3+\cdots +i_{m-1} + m/2\geq n - N - NP = N</math>. |

Since <math>N</math> is the degree of nilpotency of <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)w</math> we have that the monomial: |

Since <math>N</math> is the degree of nilpotency of <math>\mathrm{App}(u,v)w</math> we have that the monomial: |

||

: <math>(u_{22}w)^{i_1}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_2}u_{12}w\dots(u_{11}v)^{i_{m-2}}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{i_{m-1}}</math> |

: <math>(u_{22}w)^{i_1}u_{21}v(u_{11}v)^{i_2}u_{12}w\dots(u_{11}v)^{i_{m-2}}u_{12}w(u_{22}w)^{i_{m-1}}</math> |

||

| − | is null. Thus so is the monomial of type 1 we started with. |

+ | is null, thus also the monomial of type 1 we started with. |

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 08:45, 29 April 2010

The geometry of interaction, GoI in short, was defined in the early nineties by Girard as an interpretation of linear logic into operators algebra: formulae were interpreted by Hilbert spaces and proofs by partial isometries.

This was a striking novelty as it was the first time that a mathematical model of logic (lambda-calculus) didn't interpret a proof of  as a morphism from A to B[1], and proof composition (cut rule) as the composition of morphisms. Rather the proof was interpreted as an operator acting on

as a morphism from A to B[1], and proof composition (cut rule) as the composition of morphisms. Rather the proof was interpreted as an operator acting on  , that is a morphism from

, that is a morphism from  to

to  . For proof composition the problem was then, given an operator on

. For proof composition the problem was then, given an operator on  and another one on

and another one on  to construct a new operator on

to construct a new operator on  . This problem was solved by the execution formula that bares some formal analogies with Kleene's formula for recursive functions. For this reason GoI was claimed to be an operational semantics, as opposed to traditionnal denotational semantics.

. This problem was solved by the execution formula that bares some formal analogies with Kleene's formula for recursive functions. For this reason GoI was claimed to be an operational semantics, as opposed to traditionnal denotational semantics.

The first instance of the GoI was restricted to the MELL fragment of linear logic (Multiplicative and Exponential fragment) which is enough to encode lambda-calculus. Since then Girard proposed several improvements: firstly the extension to the additive connectives known as Geometry of Interaction 3 and more recently a complete reformulation using Von Neumann algebras that allows to deal with some aspects of implicit complexity

The GoI has been a source of inspiration for various authors. Danos and Regnier have reformulated the original model exhibiting its combinatorial nature using a theory of reduction of paths in proof-nets and showing the link with abstract machines; in particular the execution formula appears as the composition of two automata that interact one with the other through their common interface. Also the execution formula has rapidly been understood as expressing the composition of strategies in game semantics. It has been used in the theory of sharing reduction for lambda-calculus in the Abadi-Gonthier-Lévy reformulation and simplification of Lamping's representation of sharing. Finally the original GoI for the MELL fragment has been reformulated in the framework of traced monoidal categories following an idea originally proposed by Joyal.

Contents

|

The Geometry of Interaction as operators

The original construction of GoI by Girard follows a general pattern already mentionned in coherent semantics under the name symmetric reducibility and that was first put to use in phase semantics. First set a general space P called the proof space because this is where the interpretations of proofs will live. Make sure that P is a (not necessarily commutative) monoid. In the case of GoI, the proof space is a subset of the space of bounded operators on  .

.

Second define a particular subset of P that will be denoted by  ; then derive a duality on P: for

; then derive a duality on P: for  , u and v are dual[2], iff

, u and v are dual[2], iff  .

.

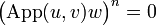

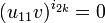

For the GoI, two dualities have proved to work; we will consider the first one: nilpotency, ie,  is the set of nilpotent operators in P. Let us explicit this: two operators u and v are dual if there is a nonegative integer n such that (uv)n = 0. Note in particular that

is the set of nilpotent operators in P. Let us explicit this: two operators u and v are dual if there is a nonegative integer n such that (uv)n = 0. Note in particular that  iff

iff  .

.

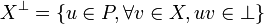

When X is a subset of P define  as the set of elements of P that are dual to all elements of X:

as the set of elements of P that are dual to all elements of X:

-

.

.

This construction has a few properties that we will use without mention in the sequel. Given two subsets X and Y of P we have:

- if

then

then  ;

;

-

;

;

-

.

.

Last define a type as a subset T of the proof space that is equal to its bidual:  . This means that

. This means that  iff for all operator

iff for all operator  , that is such that

, that is such that  for all

for all  , we have

, we have  .

.

The real work[3], is now to interpret logical operations, that is to associate a type to each formula, an object to each proof and show the adequacy lemma: if u is the interpretation of a proof of the formula A then u belongs to the type associated to A.

Preliminaries

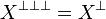

We will denote by H the Hilbert space  of sequences

of sequences  of complex numbers such that the series

of complex numbers such that the series  converges. If

converges. If  and

and  are two vectors of H their scalar product is:

are two vectors of H their scalar product is:

-

.

.

Two vectors of H are othogonal if their scalar product is nul. We will say that two subspaces are disjoint when any two vectors taken in each subspace are orthorgonal. Note that this notion is different from the set theoretic one, in particular two disjoint subspaces always have exactly one vector in common: 0.

The norm of a vector is the square root of the scalar product with itself:

-

.

.

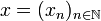

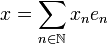

Let us denote by  the canonical hilbertian basis of H:

the canonical hilbertian basis of H:  where δkn is the Kroenecker symbol: δkn = 1 if k = n, 0 otherwise. Thus if

where δkn is the Kroenecker symbol: δkn = 1 if k = n, 0 otherwise. Thus if  is a sequence in H we have:

is a sequence in H we have:

-

.

.

An operator on H is a continuous linear map from H to H[4]. The set of (bounded) operators is denoted by  .

.

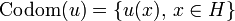

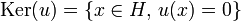

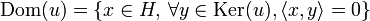

The range or codomain of the operator u is the set of images of vectors; the kernel of u is the set of vectors that are anihilated by u; the domain of u is the set of vectors orthogonal to the kernel, ie, the maximal subspace disjoint with the kernel:

-

;

;

-

;

;

-

.

.

These three sets are closed subspaces of H.

The adjoint of an operator u is the operator u * defined by  for any

for any  . Adjointness is well behaved w.r.t. composition of operators:

. Adjointness is well behaved w.r.t. composition of operators:

- (uv) * = v * u * .

A projector is an idempotent operator of norm 0 (the projector

on the null subspace) or 1, that is an operator p

such that p2 = p and  or 1. A projector is auto-adjoint and its domain is equal to its codomain.

or 1. A projector is auto-adjoint and its domain is equal to its codomain.

A partial isometry is an operator u satisfying uu * u = u; this condition entails that we also have u * uu * = u * . As a consequence uu * and uu * are both projectors, called respectively the initial and the final projector of u because their (co)domains are respectively the domain and the codomain of u:

- Dom(u * u) = Codom(u * u) = Dom(u);

- Dom(uu * ) = Codom(uu * ) = Codom(u).

The restriction of u to its domain is an isometry. Projectors are particular examples of partial isometries.

If u is a partial isometry then u * is also a partial isometry the domain of which is the codomain of u and the codomain of which is the domain of u.

If the domain of u is H that is if u * u = 1 we say that u has full domain, and similarly for codomain. If u and v are two partial isometries, the equation uu * + vv * = 1 means that the codomains of u and v are disjoint but their direct sum is H.

Partial permutations and partial isometries

We will now define our proof space which turns out to be the set of partial isometries acting as permutations on the canonical basis  .

.

More precisely a partial permutation  on

on  is a one-to-one map defined on a subset

is a one-to-one map defined on a subset  of

of  onto a subset

onto a subset  of

of  .

.  is called the domain of

is called the domain of  and

and  its codomain. Partial permutations may be composed: if ψ is another partial permutation on

its codomain. Partial permutations may be composed: if ψ is another partial permutation on  then

then  is defined by:

is defined by:

-

iff

iff  and

and  ;

;

- if

then

then  ;

;

- the codomain of

is the image of the domain:

is the image of the domain:  .

.

Partial permutations are well known to form a structure of inverse monoid that we detail now.

A partial identitie is a partial permutation 1D whose domain and codomain are both equal to a subset D on which 1D is the identity function. Partial identities are idempotent for composition.

Among partial identities one finds the identity on the empty subset, that is the empty map, that we will denote by 0 and the identity on  that we will denote by 1. This latter permutation is the neutral for composition.

that we will denote by 1. This latter permutation is the neutral for composition.

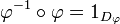

If  is a partial permutation there is an inverse partial permutation

is a partial permutation there is an inverse partial permutation  whose domain is

whose domain is  and who satisfies:

and who satisfies:

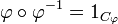

Given a partial permutation  one defines a partial isometry

one defines a partial isometry  by:

by:

In other terms if  is a sequence in

is a sequence in  then

then  is the sequence

is the sequence  defined by:

defined by:

-

if

if  , 0 otherwise.

, 0 otherwise.

We will (not so abusively) write  when

when  is undefined so that the definition of

is undefined so that the definition of  reads:

reads:

-

.

.

The domain of  is the subspace spanned by the family

is the subspace spanned by the family  and the codomain of

and the codomain of  is the subspace spanned by

is the subspace spanned by  . In particular if

. In particular if  is 1D then

is 1D then  is the projector on the subspace spanned by

is the projector on the subspace spanned by  .

.

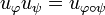

Proposition

Let  and ψ be two partial permutations. We have:

and ψ be two partial permutations. We have:

-

.

.

The adjoint of  is:

is:

-

.

.

In particular the initial projector of  is given by:

is given by:

-

.

.

and the final projector of  is:

is:

-

.

.

Projectors generated by partial identities commute:

-

.

.

Note that this entails all the other commutations of projectors:  and

and  .

.

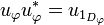

Definition

We call p-isometry a partial isometry of the form  where

where  is a partial permutation on

is a partial permutation on  . The proof space

. The proof space  is the set of all p-isometries.

is the set of all p-isometries.

In particular note that 0 is a p-isometry. The set  is a submonoid of

is a submonoid of  but it is not a subalgebra[5]. In general given

but it is not a subalgebra[5]. In general given  we don't necessarily have

we don't necessarily have  . However we have:

. However we have:

Proposition

Let  . Then

. Then  iff u and v have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains, that is:

iff u and v have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains, that is:

-

iff uu * vv * = u * uv * v = 0.

iff uu * vv * = u * uv * v = 0.

Proof. Suppose for contradiction that en is in the domains of u and v. There are integers p and q such that u(en) = ep and v(en) = eq thus (u + v)(en) = ep + eq which is not a basis vector; therefore u + v is not a p-permutation.

As a corollary note that if u + v = 0 then u = v = 0.

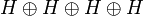

From operators to matrices: internalization/externalization

It will be convenient to view operators on H as acting on  , and conversely. For this purpose we define an isomorphism

, and conversely. For this purpose we define an isomorphism  by

by  where

where  and

and  are partial isometries given by:

are partial isometries given by:

- p(en) = e2n,

- q(en) = e2n + 1.

From the definition p and q have full domain, that is satisfy p * p = q * q = 1. On the other hand their codomains are disjoint, thus we have p * q = q * p = 0. As the sum of their codomains is the full space H we also have pp * + qq * = 1.

Note that we have choosen p and q in  . However the choice is arbitrary: any two p-isometries with full domain and disjoint codomains would do the job.

. However the choice is arbitrary: any two p-isometries with full domain and disjoint codomains would do the job.

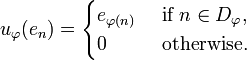

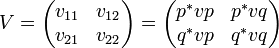

Given an operator u on H we may externalize it obtaining an operator U on  defined by the matrix:

defined by the matrix:

where the uij's are given by:

- u11 = p * up;

- u12 = p * uq;

- u21 = q * up;

- u22 = q * uq.

The uij's are called the external components of u. The externalization is functorial in the sense that if v is another operator externalized as:

then the externalization of uv is UV.

As pp * + qq * = 1 we have:

- u = (pp * + qq * )u(pp * + qq * ) = pu11p * + pu12q * + qu21p * + qu22q *

which entails that externalization is reversible, its converse being called internalization.

If we suppose that u is a p-isometry then so are the components uij's. Thus the formula above entails that the four terms of the sum have pairwise disjoint domains and pairwise disjoint codomains from which we deduce:

Proposition

If u is a p-isometry and uij are its external components then:

- u1j and u2j have disjoint domains, that is

for j = 1,2;

for j = 1,2;

- ui1 and ui2 have disjoint codomains, that is

for i = 1,2.

for i = 1,2.

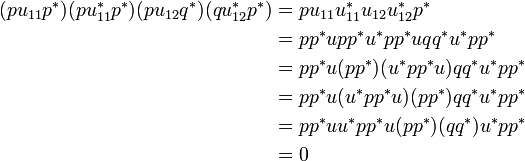

As an example of computation in  let us check that the product of the final projectors of pu11p * and pu12q * is null:

let us check that the product of the final projectors of pu11p * and pu12q * is null:

where we used the fact that all projectors in  commute, which is in particular the case of pp * and u * pp * u.

commute, which is in particular the case of pp * and u * pp * u.

Interpreting the multiplicative connectives

Recall that when u and v are p-isometries we say they are dual when uv is nilpotent, and that  denotes the set of nilpotent operators. A type is a subset of

denotes the set of nilpotent operators. A type is a subset of  that is equal to its bidual. In particular

that is equal to its bidual. In particular  is a type for any

is a type for any  . We say that X generates the type

. We say that X generates the type  .

.

The tensor and the linear application

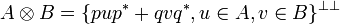

If u and v are two p-isometries summing them doesn't in general produces a p-isometry. However as pup * and qvq * have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains it is true that pup * + qvq * is a p-isometry. Given two types A and B, we thus define their tensor by:

Note the closure by bidual to make sure that we obtain a type.

From what precedes we see that  is generated by the internalizations of operators on

is generated by the internalizations of operators on  of the form:

of the form:

Remark: This so-called tensor resembles a sum rather than a product. We will stick to this terminology though because it defines the interpretation of the tensor connective of linear logic.

The linear implication is derived from the tensor by duality: given two types A and B the type  is defined by:

is defined by:

-

.

.

Unfolding this definition we get:

-

.

.

The identity

Given a type A we are to find an operator ι in type  , thus satisfying:

, thus satisfying:

-

.

.

An easy solution is to take ι = pq * + qp * . In this way we get ι(pup * + qvq * ) = qup * + pvq * . Therefore (ι(pup * + qvq * ))2 = quvq * + pvup * , from which one deduces that this operator is nilpotent iff uv is nilpotent. It is the case since u is in A and v in  .

.

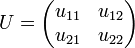

It is interesting to note that the ι thus defined is actually the internalization of the operator on  given by the matrix:

given by the matrix:

-

.

.

We will see once the composition is defined that the ι operator is the interpretation of the identity proof, as expected.

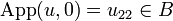

The execution formula, version 1: application

Definition

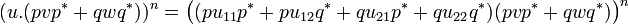

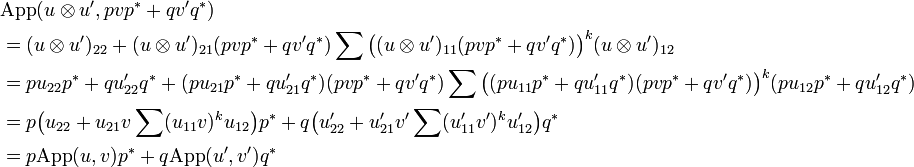

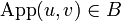

Let u and v be two operators; as above denote by uij the external components of u. If u11v is nilpotent we define the application of u to v by:

| App(u,v) = u22 + u21v | ∑ | (u11v)ku12 |

| k |

.

Note that the hypothesis that u11v is nilpotent entails that the sum

| ∑ | (u11v)k |

| k |

is actually finite. It would be enough to assume that this sum converges. For simplicity we stick to the nilpotency condition, but we should mention that weak nilpotency would do as well.

Theorem

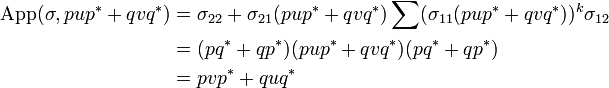

If u and v are p-isometries such that u11v is nilpotent, then App(u,v) is also a p-isometry.

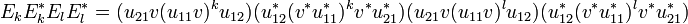

Proof. Let us note Ek = u21v(u11v)ku12. Recall that u22 and u12 being external components of the p-isometry u, they have disjoint domains. Thus it is also the case of u22 and Ek. Similarly u22 and Ek have disjoint codomains because u22 and u21 have disjoint codomains.

Let now k and l be two integers such that k > l and let us compute for example the intersection of the codomains of Ek and El:

As k > l we may write  . Let us note

. Let us note  so that

so that  . We have:

. We have:

because u11 and u12 have disjoint codomains, thus  .

.

Similarly we can show that Ek and El have disjoint domains. Therefore we have proved that all terms of the sum App(u,v) have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains. Consequently App(u,v) is a p-isometry.

Theorem

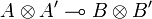

Let A and B be two types and u a p-isometry. Then the two following conditions are equivalent:

-

;

;

- for any

we have:

we have:

- u11v is nilpotent and

-

.

.

Proof. Let v and w be two p-isometries. If we compute

we get a finite sum of monomial operators of the form:

-

-

,

,

-

or

or

-

,

,

for all tuples of (nonnegative) integers  such that

such that  .

.

Each of these monomial is a p-isometry. Furthermore they have disjoint domains and disjoint codomains because their sum is the p-isometry (u.(pvp * + qwq * ))n. This entails that (u.(pvp * + qwq * ))n = 0 iff all these monomials are null.

Suppose u11v is nilpotent and consider:

-

.

.

Developping we get a finite sum of monomials of the form:

- 5.

for all tuples  such that

such that  and ki is less than the degree of nilpotency of u11v for all i.

and ki is less than the degree of nilpotency of u11v for all i.

Again as these monomials are p-isometries and their sum is the p-isometry (App(u,v)w)n, they have pairwise disjoint domains and pairwise disjoint codomains. Note that each of these monomial is equal to q * Mq where M is a monomial of type 4 above.

As before we thus have that  iff all monomials of type 5 are null.

iff all monomials of type 5 are null.

Suppose now that  and

and  . Then, since

. Then, since  (0 belongs to any type) u.(pvp * ) = pu11vp * is nilpotent, thus u11v is nilpotent.

(0 belongs to any type) u.(pvp * ) = pu11vp * is nilpotent, thus u11v is nilpotent.

Suppose further that  . Then u.(pvp * + qwq * ) is nilpotent, thus there is a N such that (u.(pvp * + qwq * ))n = 0 for any

. Then u.(pvp * + qwq * ) is nilpotent, thus there is a N such that (u.(pvp * + qwq * ))n = 0 for any  . This entails that all monomials of type 1 to 4 are null. Therefore all monomials appearing in the developpment of (App(u,v)w)N are null which proves that App(u,v)w is nilpotent. Thus

. This entails that all monomials of type 1 to 4 are null. Therefore all monomials appearing in the developpment of (App(u,v)w)N are null which proves that App(u,v)w is nilpotent. Thus  .

.

Conversely suppose for any  and

and  , u11v and App(u,v)w are nilpotent. Let P and N be their respective degrees of nilpotency and put n = N(P + 1) + N. Then we claim that all monomials of type 1 to 4 appearing in the development of (u.(pvp * + qwq * ))n are null.

, u11v and App(u,v)w are nilpotent. Let P and N be their respective degrees of nilpotency and put n = N(P + 1) + N. Then we claim that all monomials of type 1 to 4 appearing in the development of (u.(pvp * + qwq * ))n are null.

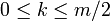

Consider for example a monomial of type 1:

with  . Note that m must be even.

. Note that m must be even.

If  for some

for some  then

then  thus our monomial is null. Otherwise if i2k < P for all k we have:

thus our monomial is null. Otherwise if i2k < P for all k we have:

thus:

-

.

.

Now if  then

then  . Otherwise

. Otherwise  thus

thus

-

.

.

Since N is the degree of nilpotency of App(u,v)w we have that the monomial:

is null, thus also the monomial of type 1 we started with.

Corollary

If A and B are types then we have:

-

.

.

As an example if we compute the application of the interpretation of the identity ι in type  to the operator

to the operator  then we have:

then we have:

-

.

.

Now recall that ι = pq * + qp * so that ι11 = ι22 = 0 and ι12 = ι21 = 1 and we thus get:

- App(ι,v) = v

as expected.

The tensor rule

Let now A,A',B and B' be types and consider two operators u and u' respectively in  and

and  . We define an operator denoted by

. We define an operator denoted by  by:

by:

Once again the notation is motivated by linear logic syntax and is contradictory with linear algebra practice since what we denote by  actually is the internalization of the direct sum

actually is the internalization of the direct sum  .

.

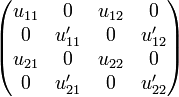

Indeed if we think of u and u' as the internalizations of the matrices:

-

and

and

then we may write:

Thus the components of  are given by:

are given by:

-

.

.

and we see that  is actually the internalization of the matrix:

is actually the internalization of the matrix:

We are now to show that if we suppose uand u' are in types  and

and  , then

, then  is in

is in  . For this we consider v and v' in respectively in A and A', so that pvp * + qv'q * is in

. For this we consider v and v' in respectively in A and A', so that pvp * + qv'q * is in  , and we show that

, and we show that  .

.

Since u and u' are in  and

and  we have that App(u,v) and App(u',v') are respectively in B and B', thus:

we have that App(u,v) and App(u',v') are respectively in B and B', thus:

-

.

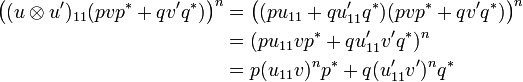

.

We know that both u11v and u'11v' are nilpotent. But we have:

Therefore  is nilpotent. So we can compute

is nilpotent. So we can compute  :

:

thus lives in  .

.

Other monoidal constructions

Contraposition

Let A and B be some types; we have:

Indeed,  means that for any v and w in respectively A and

means that for any v and w in respectively A and  we have

we have  which is exactly the definition of

which is exactly the definition of  .

.

We will denote  the operator:

the operator:

where uij is given by externalization. Therefore the externalization of  is:

is:

-

where

where  is defined by

is defined by  .

.

From this we deduce that  and that

and that  .

.

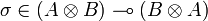

Commutativity

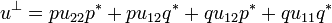

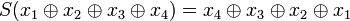

Let σ be the operator:

- σ = ppq * q * + pqp * q * + qpq * p * + qqp * p * .

One can check that σ is the internalization of the operator S on  defined by:

defined by:  . In particular the components of σ are:

. In particular the components of σ are:

- σ11 = σ22 = 0;

- σ12 = σ21 = pq * + qp * .

Let A and B be types and u and v be operators in A and B. Then pup * + qvq * is in  and as σ11.(pup * + qvq * ) = 0 we may compute:

and as σ11.(pup * + qvq * ) = 0 we may compute:

But  , thus we have shown that:

, thus we have shown that:

-

.

.

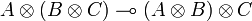

Distributivity

We get distributivity by considering the operator:

- δ = ppp * p * q * + pqpq * p * q * + pqqq * q * + qppp * p * + qpqp * q * p * + qqq * q * p *

that is similarly shown to be in type  for any types A, B and C.

for any types A, B and C.

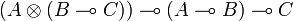

Weak distributivity

We can finally get weak distributivity thanks to the operators:

- δ1 = pppp * q * + ppqp * q * q * + pqq * q * q * + qpp * p * p * + qqpq * p * p * + qqqq * p * and

- δ2 = ppp * p * q * + pqpq * p * q * + pqqq * q * + qppp * p * + qpqp * q * p * + qqq * q * p * .

Given three types A, B and C then one can show that:

- δ1 has type

and

and

- δ2 has type

.

.

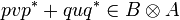

Execution formula, version 2: composition

Let A, B and C be types and u and v be operators respectively in types  and

and  .

.

As usual we will denote uij and vij the operators obtained by externalization of u and v, eg, u11 = p * up, ...

As u is in  we have that

we have that  ; similarly as

; similarly as  , thus

, thus  , we have

, we have  . Thus u22v11 is nilpotent.

. Thus u22v11 is nilpotent.

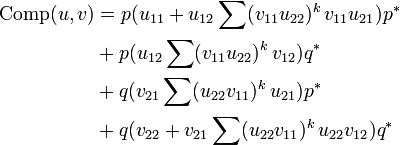

We define the operator Comp(u,v) by:

This is well defined since u11v22 is nilpotent. As an example let us compute the composition of u and ι in type  ; recall that ιij = δij, so we get:

; recall that ιij = δij, so we get:

- Comp(u,ι) = pu11p * + pu12q * + qu21p * + qu22q * = u

Similar computation would show that Comp(ι,v) = v (we use pp * + qq * = 1 here).

Coming back to the general case we claim that Comp(u,v) is in  : let a be an operator in A. By computation we can check that:

: let a be an operator in A. By computation we can check that:

- App(Comp(u,v),a) = App(v,App(u,a)).

Now since u is in  , App(u,a) is in B and since v is in

, App(u,a) is in B and since v is in  , App(v,App(u,a)) is in C.

, App(v,App(u,a)) is in C.

If we now consider a type D and an operator w in  then we have:

then we have:

- Comp(Comp(u,v),w) = Comp(u,Comp(v,w)).

Putting together the results of this section we finally have:

Theorem

Let GoI(H) be defined by:

- objects are types, ie sets A of operators satisfying:

;

;

- morphisms from A to B are operators in type

;

;

- composition is given by the formula above.

Then GoI(H) is a star-autonomous category.

The Geometry of Interaction as an abstract machine

Cite error:

<ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found