Geometry of interaction

(→The Geometry of Interaction as operators) |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

The GoI has been a source of inspiration for various authors. Danos and Regnier have reformulated the original model exhibiting its combinatorial nature using a theory of reduction of paths in proof-nets and showing the link with abstract machines; in particular the execution formula appears as the composition of two automata that interact one with the other through their common interface. Also the execution formula has rapidly been understood as expressing the composition of strategies in game semantics. It has been used in the theory of sharing reduction for lambda-calculus in the Abadi-Gonthier-Lévy reformulation and simplification of Lamping's representation of sharing. Finally the original GoI for the <math>MELL</math> fragment has been reformulated in the framework of traced monoidal categories following an idea originally proposed by Joyal. |

The GoI has been a source of inspiration for various authors. Danos and Regnier have reformulated the original model exhibiting its combinatorial nature using a theory of reduction of paths in proof-nets and showing the link with abstract machines; in particular the execution formula appears as the composition of two automata that interact one with the other through their common interface. Also the execution formula has rapidly been understood as expressing the composition of strategies in game semantics. It has been used in the theory of sharing reduction for lambda-calculus in the Abadi-Gonthier-Lévy reformulation and simplification of Lamping's representation of sharing. Finally the original GoI for the <math>MELL</math> fragment has been reformulated in the framework of traced monoidal categories following an idea originally proposed by Joyal. |

||

| − | |||

| − | = The Geometry of Interaction as an abstract machine = |

||

= The Geometry of Interaction as operators = |

= The Geometry of Interaction as operators = |

||

| Line 25: | Line 23: | ||

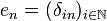

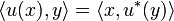

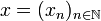

Let us denote by <math>(e_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> the canonical hilbertian basis of <math>H = \ell^2</math>; <math>e_n</math> is the sequence containing only 0's but at the <math>n</math>'s position where its value is <math>1</math>: <math>e_n = (\delta_{in})_{i\in\mathbb{N}}</math> where <math>\delta_{in}</math> is the standard Kroenecker function. Recall that the adjoint of an operator <math>u</math> is the operator <math>u^*</math> defined by <math>\langle u(x), y\rangle = \langle x, u^*(y)\rangle</math> for any <math>x,y\in H</math>. |

Let us denote by <math>(e_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> the canonical hilbertian basis of <math>H = \ell^2</math>; <math>e_n</math> is the sequence containing only 0's but at the <math>n</math>'s position where its value is <math>1</math>: <math>e_n = (\delta_{in})_{i\in\mathbb{N}}</math> where <math>\delta_{in}</math> is the standard Kroenecker function. Recall that the adjoint of an operator <math>u</math> is the operator <math>u^*</math> defined by <math>\langle u(x), y\rangle = \langle x, u^*(y)\rangle</math> for any <math>x,y\in H</math>. |

||

| − | A ''partial isometry'' is an operator <math>u</math> satisfying <math>uu^* u = u</math>; as a consequence <math>uu^*</math> is a projector the range of which is the range of <math>u</math>; we will call ''codomain'' the range of <math>u</math>. Similarly <math>u^* u</math> is also a projector the range of which is the ''domain'' of <math>u</math> (which is orthogonal to the kernel of <math>u</math>). The domain and the codomain of <math>u</math> are both closed subspace of <math>H</math> and <math>u</math> restricted to its domain is an isometry. If the domain <math>u</math> is <math>H</math> that is if <math>u^* u = 1</math> we say that <math>u</math> has ''full domain'', and similarly for codomain. |

+ | A ''partial isometry'' is an operator <math>u</math> satisfying <math>uu^* u = u</math>; as a consequence <math>uu^*</math> is a projector the range of which is the range of <math>u</math>; we will call ''codomain'' the range of <math>u</math>. Similarly <math>u^* u</math> is also a projector the range of which is the ''domain'' of <math>u</math>, defined to be the orthogonal subspace of the kernel of <math>u</math>. The domain and the codomain of <math>u</math> are both closed subspace of <math>H</math> and <math>u</math> restricted to its domain is an isometry. If the domain of <math>u</math> is <math>H</math> that is if <math>u^* u = 1</math> we say that <math>u</math> has ''full domain'', and similarly for codomain. |

If <math>u</math> is a partial isometry then <math>u^*</math> is also a partial isometry the domain of which is the codomain of <math>u</math> and the codomain of which is the domain of <math>u</math>. |

If <math>u</math> is a partial isometry then <math>u^*</math> is also a partial isometry the domain of which is the codomain of <math>u</math> and the codomain of which is the domain of <math>u</math>. |

||

| Line 31: | Line 29: | ||

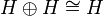

If <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are two partial isometries, the equation <math>uu^* + vv^* = 1</math> means that the codomains of <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are orthogonal and that their direct sum is <math>H</math>. |

If <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are two partial isometries, the equation <math>uu^* + vv^* = 1</math> means that the codomains of <math>u</math> and <math>v</math> are orthogonal and that their direct sum is <math>H</math>. |

||

| − | We shall define a number of operators on <math>H</math> by describing their action on the basis <math>(e_n)</math>; actually most of the operators that are used to interpret logical operations will turn out to be defined as partial permutations on the basis, which in particular entails that they are partial isometries. More precisely given a partial permutation <math>\varphi</math> on <math>\mathbb{N}</math>, that is a one-to-one function from a subset of <math>\mathbb{N}</math> into <math>\mathbb{N}</math> one define the partial isometry <math>u_\varphi</math> by <math>u_\varphi(e_n) = e_{\varphi(n)}</math> if <math>\varphi(n)</math> is defined, <math>0</math> otherwise. |

+ | === Partial permutations and partial isometries === |

| + | |||

| + | It turns out that most of the operators needed to interpret logical operations are generated by ''partial permutations'' on the basis, which in particular entails that they are partial isometries. |

||

| + | |||

| + | More precisely a partial permutation <math>\varphi</math> on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> is a function defined on a subset <math>D_\varphi</math> of <math>\mathbb{N}</math>, the ''domain'' of <math>\varphi</math>, which is one-to-one onto a subset <math>C_\varphi</math> of <math>\mathbb{N}</math>, the ''codomain'' of <math>\varphi</math>. Partial permutations may be composed: if <math>\psi</math> is another partial permutation on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> then <math>\varphi\circ\psi</math> is defined by: |

||

| + | |||

| + | : <math>n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math> iff <math>n\in D_\psi</math> and <math>\psi(n)\in D_\varphi</math>; |

||

| + | : if <math>n\in D_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math> then <math>\varphi\circ\psi(n) = \varphi(\psi(n))</math>; |

||

| + | : the codomain of <math>\varphi\circ\psi</math> is the image of the domain. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Partial permutations are well known to form a structure of ''inverse monoid that we detail now. |

||

| + | |||

| + | A ''partial identitie'' is a partial permutation <math>1_D</math> whose domain and codomain are both equal to a subset <math>D</math> on which <math>1_D</math> is the identity function. Among partial identities one finds the identity on the empty subset, that is the empty map, that we will denote as <math>0</math> and the identity on <math>\mathbb{N}</math> that we will denote <math>1</math>. This latter permutation is the neutral for composition. |

||

| + | |||

| + | If <math>\varphi</math> is a partial permutation there is an inverse partial permutation <math>\varphi^{-1}</math> whose domain is <math>D_{\varphi^{-1}} = C_{\varphi}</math> and who satisfies: |

||

| + | |||

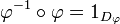

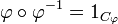

| + | : <math>\varphi^{-1}\circ\varphi = 1_{D_\varphi}</math> |

||

| + | : <math>\varphi\circ\varphi^{-1} = 1_{C_\varphi}</math> |

||

| + | |||

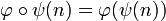

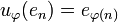

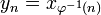

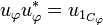

| + | Given a partial permutation <math>\varphi</math> one defines a partial isometry <math>u_\varphi</math> by <math>u_\varphi(e_n) = e_{\varphi(n)}</math> if <math>n\in D_\varphi</math>, <math>0</math> otherwise. In other terms if <math>x=(x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> is a sequence in <math>\ell^2</math> then <math>u_\varphi(x)</math> is the sequence <math>(y_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}</math> defined by: |

||

| + | : <math>y_n = x_{\varphi^{-1}(n)}</math> if <math>n\in C_\varphi</math>, <math>0</math> otherwise. |

||

| + | |||

| + | The domain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is the subspace spaned by the family <math>(e_n)_{n\in D_\varphi}</math> and the codomain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is the subspace spaned by <math>(e_n)_{n\in C_\varphi}</math>. As a particular case if <math>\varphi</math> is <math>1_D</math> the partial identity on <math>D</math> then <math>u_\varphi</math> is the projector on the subspace spaned by <math>(e_n)_{n\in D}</math>. |

||

| + | |||

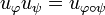

| + | If <math>\psi</math> is another partial permutation then we have: |

||

| + | : <math>u_\varphi u_\psi = u_{\varphi\circ\psi}</math>. |

||

| + | |||

| + | If <math>\varphi</math> is a partial permutation then the adjoint of <math>u_\varphi</math> is: |

||

| + | : <math>u_\varphi^* = u_{\varphi^{-1}}</math>. |

||

| + | |||

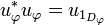

| + | In particular the projector on the domain of <math>u_{\varphi}</math> is given by: |

||

| + | : <math>u^*_\varphi u_\varphi = u_{1_{D_\varphi}}</math>. |

||

| + | |||

| + | and similarly the projector on the codomain of <math>u_\varphi</math> is: |

||

| + | : <math>u_\varphi u_\varphi^* = u_{1_{C_\varphi}}</math>. |

||

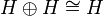

== Interpreting the tensor == |

== Interpreting the tensor == |

||

| Line 42: | Line 40: | ||

This is actually arbitrary, any two partial isometries <math>p,q</math> with full domain and such that the sum of their codomains is <math>H</math> would do the job. |

This is actually arbitrary, any two partial isometries <math>p,q</math> with full domain and such that the sum of their codomains is <math>H</math> would do the job. |

||

| − | From the definition <math>p</math> and <math>q</math> have full domain, that is satisfy <math>p^* p = q^* q = 1</math>. On the other hand their codomains are orthogonal, thus we have <math>p^* q = q^* p = 0</math>. Note that we also have <math>pp^* + qq^* = 1</math> although this property is not needed in the sequel. |

+ | We shall From the definition <math>p</math> and <math>q</math> have full domain, that is satisfy <math>p^* p = q^* q = 1</math>. On the other hand their codomains are orthogonal, thus we have <math>p^* q = q^* p = 0</math>. Note that we also have <math>pp^* + qq^* = 1</math> although this property is not needed in the sequel. |

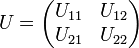

Let <math>U</math> be an operator on <math>H\oplus H</math>. We can write <math>U</math> as a matrix: |

Let <math>U</math> be an operator on <math>H\oplus H</math>. We can write <math>U</math> as a matrix: |

||

| Line 66: | Line 64: | ||

0 & v |

0 & v |

||

\end{pmatrix}</math> |

\end{pmatrix}</math> |

||

| + | |||

| + | = The Geometry of Interaction as an abstract machine = |

||

Revision as of 11:05, 28 March 2010

The geometry of interaction, GoI in short, was defined in the early nineties by Girard as an interpretation of linear logic into operators algebra: formulae were interpreted by Hilbert spaces and proofs by partial isometries.

This was a striking novelty as it was the first time that a mathematical model of logic (lambda-calculus) didn't interpret a proof of  as a morphism from (the space interpreting) A to (the space interpreting) B and proof composition (cut rule) as the composition of morphisms. Rather the proof was interpreted as an operator acting on (the space interpreting)

as a morphism from (the space interpreting) A to (the space interpreting) B and proof composition (cut rule) as the composition of morphisms. Rather the proof was interpreted as an operator acting on (the space interpreting)  , that is a morphism from

, that is a morphism from  to

to  . For proof composition the problem was then, given an operator on

. For proof composition the problem was then, given an operator on  and another one on

and another one on  to construct a new operator on

to construct a new operator on  . This problem was originally expressed as a feedback equation solved by the execution formula. The execution formula has some formal analogies with Kleene's formula for recursive functions, which allowed to claim that GoI was an operational semantics, as opposed to traditionnal denotational semantics.

. This problem was originally expressed as a feedback equation solved by the execution formula. The execution formula has some formal analogies with Kleene's formula for recursive functions, which allowed to claim that GoI was an operational semantics, as opposed to traditionnal denotational semantics.

The first instance of the GoI was restricted to the MELL fragment of linear logic (Multiplicative and Exponential fragment) which is enough to encode lambda-calculus. Since then Girard proposed several improvements: firstly the extension to the additive connectives known as Geometry of Interaction 3 and more recently a complete reformulation using Von Neumann algebras that allows to deal with some aspects of implicit complexity

The GoI has been a source of inspiration for various authors. Danos and Regnier have reformulated the original model exhibiting its combinatorial nature using a theory of reduction of paths in proof-nets and showing the link with abstract machines; in particular the execution formula appears as the composition of two automata that interact one with the other through their common interface. Also the execution formula has rapidly been understood as expressing the composition of strategies in game semantics. It has been used in the theory of sharing reduction for lambda-calculus in the Abadi-Gonthier-Lévy reformulation and simplification of Lamping's representation of sharing. Finally the original GoI for the MELL fragment has been reformulated in the framework of traced monoidal categories following an idea originally proposed by Joyal.

Contents |

The Geometry of Interaction as operators

The original construction of GoI by Girard follows a general pattern already mentionned in coherent semantics under the name symmetric reducibility. First set a general space in which the interpretations of proofs will live; here, in the case of GoI, the space is the space of bounded operators on  .

.

Second define a suitable duality on this space that will be denoted as  . For the GoI, two dualities have proved to work, the first one being nilpotency: two operators u and v are dual if uv is nilpotent, that is, if there is an nonegative integer n such that (uv)n = 0.

. For the GoI, two dualities have proved to work, the first one being nilpotency: two operators u and v are dual if uv is nilpotent, that is, if there is an nonegative integer n such that (uv)n = 0.

Last define a type as a subset T of the proof space that is equal to its bidual:  . In the case of GoI this means that

. In the case of GoI this means that  iff for all operator v, if

iff for all operator v, if  , that is if u'v is nilpotent for all

, that is if u'v is nilpotent for all  , then

, then  , that is uv is nilpotent.

, that is uv is nilpotent.

It remains now to interpret logical operations, that is associate a type to each formula, an object to each proof and show the adequacy lemma, if u is the interpretation of a proof of the formula A then u belongs to the type associated to A.

Preliminaries

We begin by a brief tour of the operations on H that will be used in the sequel.

Let us denote by  the canonical hilbertian basis of

the canonical hilbertian basis of  ; en is the sequence containing only 0's but at the n's position where its value is 1:

; en is the sequence containing only 0's but at the n's position where its value is 1:  where δin is the standard Kroenecker function. Recall that the adjoint of an operator u is the operator u * defined by

where δin is the standard Kroenecker function. Recall that the adjoint of an operator u is the operator u * defined by  for any

for any  .

.

A partial isometry is an operator u satisfying uu * u = u; as a consequence uu * is a projector the range of which is the range of u; we will call codomain the range of u. Similarly u * u is also a projector the range of which is the domain of u, defined to be the orthogonal subspace of the kernel of u. The domain and the codomain of u are both closed subspace of H and u restricted to its domain is an isometry. If the domain of u is H that is if u * u = 1 we say that u has full domain, and similarly for codomain.

If u is a partial isometry then u * is also a partial isometry the domain of which is the codomain of u and the codomain of which is the domain of u.

If u and v are two partial isometries, the equation uu * + vv * = 1 means that the codomains of u and v are orthogonal and that their direct sum is H.

Partial permutations and partial isometries

It turns out that most of the operators needed to interpret logical operations are generated by partial permutations on the basis, which in particular entails that they are partial isometries.

More precisely a partial permutation  on

on  is a function defined on a subset

is a function defined on a subset  of

of  , the domain of

, the domain of  , which is one-to-one onto a subset

, which is one-to-one onto a subset  of

of  , the codomain of

, the codomain of  . Partial permutations may be composed: if ψ is another partial permutation on

. Partial permutations may be composed: if ψ is another partial permutation on  then

then  is defined by:

is defined by:

-

iff

iff  and

and  ;

;

- if

then

then  ;

;

- the codomain of

is the image of the domain.

is the image of the domain.

Partial permutations are well known to form a structure of inverse monoid that we detail now.

A partial identitie is a partial permutation 1D whose domain and codomain are both equal to a subset D on which 1D is the identity function. Among partial identities one finds the identity on the empty subset, that is the empty map, that we will denote as 0 and the identity on  that we will denote 1. This latter permutation is the neutral for composition.

that we will denote 1. This latter permutation is the neutral for composition.

If  is a partial permutation there is an inverse partial permutation

is a partial permutation there is an inverse partial permutation  whose domain is

whose domain is  and who satisfies:

and who satisfies:

Given a partial permutation  one defines a partial isometry

one defines a partial isometry  by

by  if

if  , 0 otherwise. In other terms if

, 0 otherwise. In other terms if  is a sequence in

is a sequence in  then

then  is the sequence

is the sequence  defined by:

defined by:

-

if

if  , 0 otherwise.

, 0 otherwise.

The domain of  is the subspace spaned by the family

is the subspace spaned by the family  and the codomain of

and the codomain of  is the subspace spaned by

is the subspace spaned by  . As a particular case if

. As a particular case if  is 1D the partial identity on D then

is 1D the partial identity on D then  is the projector on the subspace spaned by

is the projector on the subspace spaned by  .

.

If ψ is another partial permutation then we have:

-

.

.

If  is a partial permutation then the adjoint of

is a partial permutation then the adjoint of  is:

is:

-

.

.

In particular the projector on the domain of  is given by:

is given by:

-

.

.

and similarly the projector on the codomain of  is:

is:

-

.

.

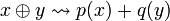

Interpreting the tensor

The first step is, given two types A and B, to construct the type  . For this purpose we will define an isomorphism

. For this purpose we will define an isomorphism  by

by  where

where  and

and  are partial isometries given by:

are partial isometries given by:

- p(en) = e2n,

- q(en) = e2n + 1.

This is actually arbitrary, any two partial isometries p,q with full domain and such that the sum of their codomains is H would do the job.

We shall From the definition p and q have full domain, that is satisfy p * p = q * q = 1. On the other hand their codomains are orthogonal, thus we have p * q = q * p = 0. Note that we also have pp * + qq * = 1 although this property is not needed in the sequel.

Let U be an operator on  . We can write U as a matrix:

. We can write U as a matrix:

where each Uij operates on H.

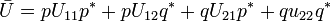

Now through the isomorphism  we may transform U into the operator

we may transform U into the operator  on H defined by:

on H defined by:

-

.

.

We call  the internalization of U.

the internalization of U.

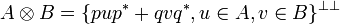

Given A and B two types, we define their tensor by:

From what precedes we see that  is generated by the internalizations of operators on

is generated by the internalizations of operators on  of the form:

of the form: